Key Considerations in Forming Private Funds

By Dominic M. Hulse, Partner, Snell & Wilmer L.L.P.*

June 8, 2023

The private fund industry has undergone significant growth over the past decade, with net assets reported by advisers exceeding $14 trillion as of the second quarter of 2022.[i] Utilizing private funds to raise capital remains an attractive option for prospective fund managers, given the relatively low barriers to entry, and reduced regulatory burdens compared with public securities offerings or registered mutual funds.

The private fund industry has undergone significant growth over the past decade, with net assets reported by advisers exceeding $14 trillion as of the second quarter of 2022.[i] Utilizing private funds to raise capital remains an attractive option for prospective fund managers, given the relatively low barriers to entry, and reduced regulatory burdens compared with public securities offerings or registered mutual funds.

However, new entrants to the private fund market should be aware that such offerings are not free from regulation, and complexities in the structuring and offering of funds should be carefully considered.

The SEC also continues to scrutinize the industry, both from an examination and enforcement[ii] and regulatory perspective.

This article examines some of the key issues that managers should consider in the formation, management, and ongoing offering of private funds.

Regulatory Overview

Managers seeking to raise private funds must understand the regulatory requirements that apply to them when structuring a vehicle. At a federal level, these can be broadly categorized into four areas:

- whether the offering of interests in the fund triggers registration requirements under the Securities Act of 1933 (the Securities Act);

- whether the offering of the fund triggers registration requirements under the Investment Company Act of 1940 (the 1940 Act);

- whether the management of the fund triggers registration requirements under the Investment Advisers Act of 1940 (the Advisers Act); and

- whether the sale of interests in the fund triggers registration requirements under the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 (the “Exchange Act”).

Depending on its proposed use of derivative instruments in a strategy, a manager may also need to consider the application of the Commodity Exchange Act of 1936 (the CEA).[iii]

Securities Act Considerations

Under the Securities Act, an offer and sale of securities must either be registered with the SEC or offered pursuant to an available exemption. When a fund accepts investors, it is an issuer engaged in the offer and sale of securities. Given the costs, disclosure burdens, and compliance obligations associated with a public offering, managers often seek to avoid issuer registration.

The most common exemption from registration relied upon by private fund managers is the private placement exemption. Under Section 4(a)(2) of the Securities Act, the obligation to register an offer and sale of securities does not apply to an issuer that is not involved in a public offering. Uncertainty around what it meant to engage in “transactions by an issuer not involving any public offering” ultimately led the SEC to adopt Regulation D under the Securities Act,[iv] which provides a non-exclusive safe harbor for issuers engaged in a private offering.

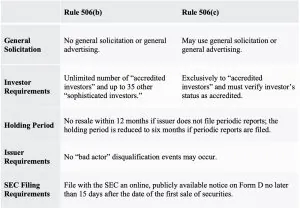

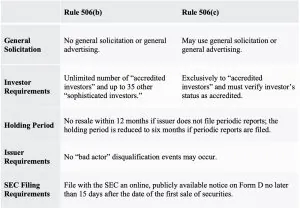

Rule 506[v] of Regulation D provides the most utilized exemptions for issuers as there is no limitation on the amount of capital that a fund may raise. The main features of the rules are set out in the table below.

The primary requirement under both Rule 506(b) and Rule 506(c) is that investors must qualify as an “accredited investor” as defined in Regulation D.[vi] An “accredited investor” is a person or entity that (among other categories):

- has an annual income of at least $200,000 (or $300,000 if combined with a spouse’s income) for the last two years with the expectation of earning the same or higher income in the current year;

- is a knowledgeable employee of the fund or holds a valid Series 7, 65 or 82 license;

- has a net worth of $1 million or more, either individually or together with a spouse, but excluding the value of a primary residence; or

- is an entity that is an organization with assets or investments exceeding $5 million or its equity owners are accredited investors.

Historically, funds could only be offered in reliance on Rule 506(b), which permitted an issuer to offer securities without registration, provided the issuer did not engage in a general solicitation. A general solicitation has been broadly defined to include any advertisement, article, notice, or other communication published in any newspaper, magazine, or similar media or broadcast over television, radio, or the Internet (or other communications devices), and any seminar or meeting whose attendees have been invited by any general solicitation or general advertising.

The restrictions on general advertising were relaxed following the adoption of Rule 506(c) following the passage of the Jumpstart Our Business Startups (JOBS) Act in 2012. Rule 506(c) permits an issuer to engage in a general solicitation of investors, provided the issuer takes reasonable steps to verify a prospective investor’s status as an “accredited investor.” Rule 506(c) sets out a non-exclusive safe harbor of steps that an issuer may take to verify an investor’s status. These require the investor to provide evidence of their income and net worth or provide a written verification of their status from a broker-dealer, investment adviser, attorney, or certified public accountant. This is in contrast to the requirements under Rule 506(b) where an issuer, absent knowledge to the contrary, may rely on the representation of an investor as to their status in a subscription agreement.

1940 Act Considerations

The next item for a prospective fund manager to consider is whether the creation of the fund triggers registration requirements under the 1940 Act. Generally, any issuer that is or holds itself out as being primarily engaged in the business of investing, reinvesting, or trading in securities is an investment company under the 1940 Act.[vii] As with a public securities offering, the management of a registered investment company involves up-front and ongoing expenses, public disclosures, and increased regulatory compliance obligations, such as requirements for independent directors, prohibitions of affiliated transactions, and a myriad of other regulations.

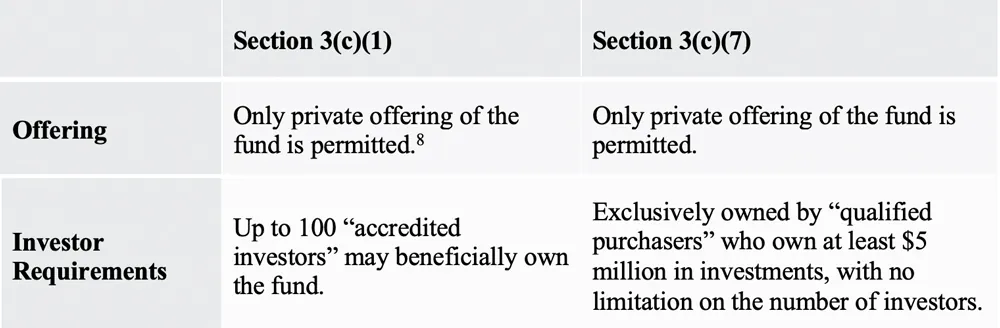

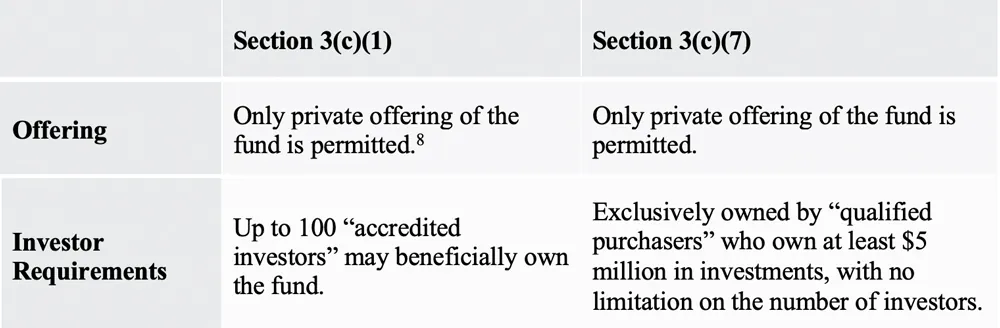

The 1940 Act contains various exemptions from the broad definition of an investment company. The most commonly relied upon exemptions for private equity, venture capital, and hedge funds are found under Section 3(c)(1) and Section 3(c)(7) of the 1940 Act. As with Rule 506, these exemptions are based on who the investors are, rather than the assets that the fund invests in.

Section 3(c)(1) of the 1940 Act excludes from the definition of an investment company any issuer whose outstanding securities are beneficially owned by not more than 100 persons and that is not making and does not presently propose to make a public offering of its securities. While the “accredited investor” status required by Rule 506 of Regulation D still applies, there is no additional status requirement for the investor, such as a net worth or other sophistication standard. While Section 3(c)(1) ostensibly appears to be an attractive option for sponsors given its simplicity, there are detailed requirements that should be considered when counting investors for purposes of the 100 beneficial owner limit.

Section 3(c)(7) of the 1940 Act excludes from the definition of an investment company any issuer of which the outstanding securities are owned exclusively by persons who, at the time of the acquisition of such securities, are qualified purchasers, and which is not making and does not at that time propose to make a public offering of such securities. A “qualified purchaser” generally is an institution with at least $25 million in investments, or a high-net-worth or ultra-high-net-worth individual with at least $5 million in investments. Again, the calculation of a prospective investor’s “investments” is complex and will need to be determined with respect to each investor’s individual circumstances.[ix]

A third exemption commonly relied upon by fund sponsors is set out under Section 3(c)(5) of the 1940 Act. Unlike Section 3(c)(1) or Section 3(c)(7), this is based on the assets the fund invests in rather than the number or status of its investors. Section 3(c)(5) excludes from the definition of an investment company any issuer that is: (i) not engaged in the business of issuing redeemable securities, face-amount certificates of the installment type or periodic payment plan certificates, and (ii) primarily engaged in one or more of the following businesses:

- purchasing or otherwise acquiring notes, drafts, acceptances, open accounts receivable, and other obligations representing part or all of the sales price of merchandise, insurance, and services;

- making loans to manufacturers, wholesalers, and retailers of, and to prospective purchasers of, specified merchandise, insurance, and services; and

- purchasing or otherwise acquiring mortgages and other liens on and interests in real estate.

The third prong of the exclusion has led to real estate managers and developers seeking to raise equity capital to rely on the exemption. However, as with other exemptions, care should be taken to ensure that the fund meets detailed “qualifying interests” tests and maintains the appropriate exposure to real property assets and real estate related interests, as articulated by the SEC staff in no-action relief.[x] The requirements of Rule 506 related to solicitation would also still apply, and investors must meet the “accredited investor” standard.

Advisers Act Considerations

Section 202(a)(11)[xi] of the Advisers Act defines an investment adviser as any person or firm who, for compensation, engages in the business of advising others as to the value of securities or as to the advisability of investing in, purchasing, or selling securities or who, for compensation and as part of a regular business, issues or promulgates analyses or reports concerning securities.

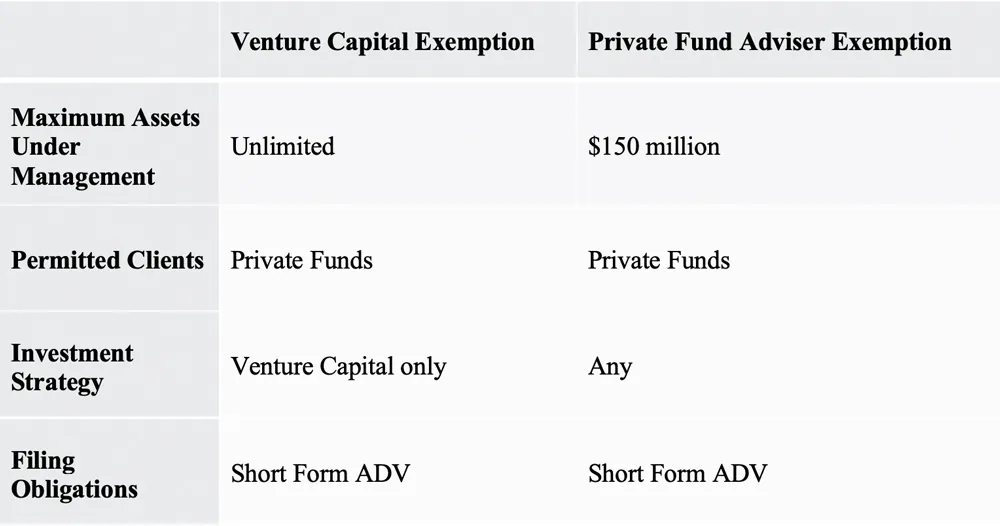

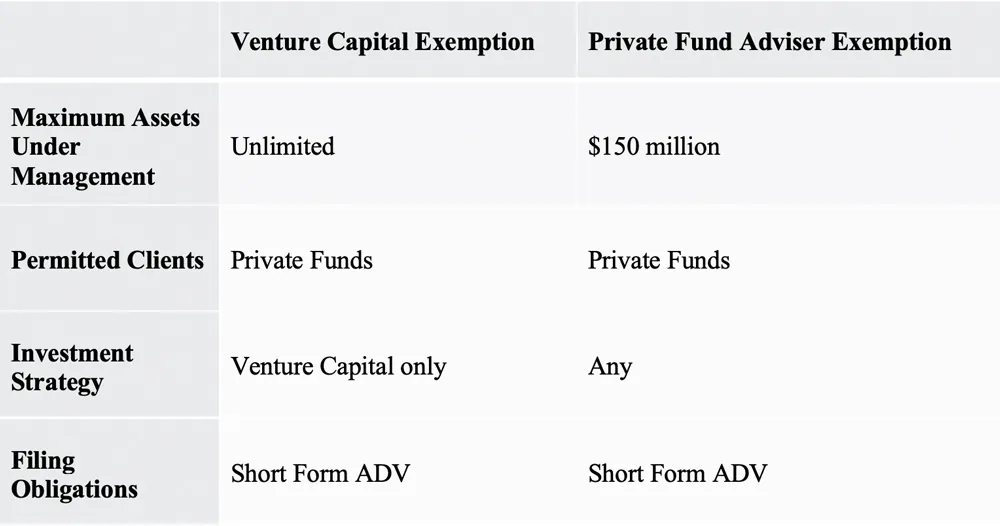

All investment advisers must register with the SEC or applicable state securities regulator unless an exemption is available. Two commonly utilized exemptions are found under Advisers Act Rule 203(l)-1 (the Venture Capital Exemption)[xii] and Rule 203(m)-1 (the Private Fund Adviser Exemption).[xiii] These exemptions are available to managers of private funds. A “private fund” is defined in Section 202(a)(29) of the Advisers Act as “an issuer that would be an investment company, as defined in section 3 of the [1940 Act] but for section 3(c)(1) or 3(c)(7) of that Act.”

The key components of the exemptions are outlined below.

Fund managers relying on the Private Fund Adviser Exemption are exempt from SEC registration where they (i) have no client that is a U.S. person except for one or more qualifying private funds, and (ii) all assets managed by the investment adviser at a place of business in the U.S. are solely attributable to private fund assets, the total value of which is less than $150 million. Managers providing advisory services to both private funds and separate account clients are not permitted to rely on the exemption.

An adviser with a principal office and place of business outside the U.S. that has no client that is a U.S. person, except for qualifying private funds managed from outside the U.S., is not subject to the $150 million threshold.

Fund managers relying on the Venture Capital Exemption are exempt from registration where they advise solely “venture capital funds.” A venture capital fund is a private fund that:

- represents to investors and potential investors that it pursues a venture capital strategy;

- invests at least 80% of its assets in “qualifying investments,” which generally are equity securities of privately held companies (other than private funds) that are issued directly to the fund;

- does not borrow or provide guarantees for more than 15% of its aggregate capital contributions and uncalled committed capital;

- engages in any borrowing for a non-renewable term of 120 or fewer calendar days; and

- prohibits investors from withdrawing or redeeming their interests except in extraordinary circumstances.

An entity or person meeting the definition of an investment adviser that does not qualify for a registration exemption under the Advisers Act must register with the appropriate regulatory authority. Absent qualification under an exemption, an adviser that has $100 million or more of regulatory assets under management must register with the SEC, while an adviser that has less than $25 million of regulatory assets under management must register with the securities regulator of the state in which it has its principal office or place of business (subject to state-specific rules). A mid-sized adviser (i.e., one that has $25 million to $100 million of regulatory assets under management) must register with the SEC if it (i) is not required to be registered as an adviser with the state securities authority in the state where it maintains its principal office and place of business, or (ii) is not subject to examination as an adviser by the state where it maintains its principal office and place of business. Most states have also adopted a form of the Private Fund Adviser Exemption and the Venture Capital Exemption.

While fund managers relying on either the Private Fund Adviser Exemption or the Venture Capital Exemption are not subject to the full regulatory requirements of the Advisers Act, they are still subject to the anti-fraud provisions of federal securities laws (as discussed below), and must make periodic filings of a shortened Form ADV Part 1 with the SEC.

In addition, a private fund adviser may only charge performance fees to a private fund if its investors are qualified clients under Rule 205-3 of the Advisers Act, which includes: individuals with $1,100,000 of assets under management with the adviser or have $2,200,000 in net worth (less the primary residence); persons who are “qualified purchasers”; and “knowledgeable employees” or executive officers, directors, or persons in a similar capacity of the investment adviser.

Finally, registered advisers must file Form PF under Advisers Act 204(b)-1 if the adviser manages private fund assets of at least $150 million.

Exchange Act Considerations

The final regulatory issue that a prospective fund manager should consider is whether selling interests in a private fund triggers registration requirements under the Exchange Act. Section 3(a)(4)(A) of the Exchange Act defines a broker as “any person engaged in the business of effecting transactions in securities for the account of others.” This has been broadly interpreted to potentially capture finders, placement agents, marketers, and internal sales personnel.

Section 15(a)(1) of the Exchange Act generally makes it unlawful for any broker or dealer to “effect any transactions in, or to induce or attempt to induce the purchase or sale of, any security” unless that broker or dealer is registered with the SEC in accordance with Section 15(b) of the Exchange Act. Most “brokers” and “dealers” engaging in regulated activity must then register with the SEC and join FINRA or another self-regulatory organization.

As such, a manager attempting to market and sell interests in its newly formed fund is potentially engaging in registerable activity as a broker-dealer.

A limited “issuer” exemption is provided by Rule 3a4-1 of the Exchange Act[xiv] which exempts “associated persons” of an issuer from being deemed a broker if such person

- is not subject to a statutory disqualification, as that term is defined in Section 3(a)(39) of the Exchange Act, at the time of his participation;

- is not compensated in connection with his participation by the payment of commissions or other remuneration based either directly or indirectly on transactions in securities;

- is not at the time of his participation an associated person of a broker or dealer; and

- meets one of the following (or other) conditions: (i) restricts their activity to transactions with certain institutional entities; or (ii) performs substantial other duties otherwise than in connection with transactions in securities, was not registered with a broker-dealer in the past 12 months, and does not participate in selling an offering of securities for any issuer more than once every 12 months.

Given the limited nature of the issuer exemption, and the broad application of the definition of a broker, many prospective managers will engage a “managing broker.” Managing brokers are third party FINRA-licensed broker-dealers who will act as a broker with respect to a fund offering utilizing registered representatives.

Marketing a Private Fund

General Solicitation

Once a prospective manager has identified the registration requirements or available exemptions in connection with the formation, offering, and management of a fund, it must also consider the regulatory framework governing its marketing activities.

For a manager seeking to rely on Rule 506(b) of Regulation D, it may not engage in a “general solicitation” of investors, as discussed above. A mechanism that a manager may utilize to avoid being deemed to have engaged in a general solicitation is to limit marketing to prospective investors with whom it has a pre-existing substantive relationship.

A pre-existing relationship is one which was formed before a securities offering commenced, or was established through a registered broker-dealer or investment adviser before the registered broker-dealer or investment adviser participated in the offering. The pre-existing relationship must be of some duration and substance.

A substantive relationship is formed when the entity offering securities (i.e., the company or its broker-dealer or investment adviser) has sufficient information to evaluate and evaluates a potential investor’s status as an accredited investor.

Marketing Rule

On November 4, 2022, amendments to Rule 206(4)-1 of the Advisers Act (the Marketing Rule)[xv] came into effect for all registered investment advisers (including those to private funds). While a substantive discussion of the Marketing Rule is beyond the scope of this article, certain provisions are instructive to both registered and unregistered advisers seeking to market private funds.

Specifically, the Marketing Rule identified seven key principles-based anti-fraud prohibitions. An adviser may not utilize advertisements that:

- include any untrue statement of a material fact, or omit to state a material fact necessary in order to make the statement made, in the light of the circumstances under which it was made, not misleading;

- include a material statement of fact that the adviser does not have a reasonable basis for believing it will be able to substantiate upon demand by the SEC;

- include information that would reasonably be likely to cause an untrue or misleading implication or inference to be drawn concerning a material fact relating to the investment adviser;

- discuss any potential benefits to clients or investors connected with or resulting from the investment adviser’s services or methods of operation without providing fair and balanced treatment of any material risks or material limitations associated with the potential benefits;

- include a reference to specific investment advice provided by the investment adviser where such investment advice is not presented in a manner that is fair and balanced;

- include or exclude performance results, or present performance time periods, in a manner that is not fair and balanced; or

- otherwise be materially misleading.

Given that fund managers relying on exemptions from registration under Federal securities laws are still subject to their broad anti-fraud provisions, they would be wise to examine their marketing activities in light of the above prohibitions. Fund managers must also consider rules around gross and net performance under the Marketing Rule and SEC staff guidance.[xvi]

Anti-Fraud Provisions

All of the primary securities laws discussed above contain broad anti-fraud provisions. For example, Rule 10b-5 of the Exchange Act provides “it shall be unlawful for any person… (a) to employ any device, scheme, or artifice to defraud, (b) to make any untrue statement of a material fact or to omit to state a material fact necessary in order to make the statements made, in the light of the circumstances under which they were made, not misleading, or (c) to engage in any act, practice or course of business which operates or would operate as a fraud or deceit upon any person, in connection with the purchase or sale of any security.”

A primary goal in the introduction of U.S. securities laws was to prohibit deceit and manipulation of investors. As such, most of the anti-fraud provisions of the U.S. securities laws apply to all issuers of securities, whether or not such market participants are otherwise required to register and whether or not provisions of such laws other than the anti-fraud provisions apply to them. Fund managers should be mindful of potential fraud claims, even constructive fraud claims based on negligence, during the formation and operation of their funds.

Regulatory Horizon

The regulatory landscape in which private fund managers operate is far from static. The SEC recently proposed a wide-ranging private fund adviser rule that would have far reaching implications for the industry if adopted.[xvii] Specifically, it would require registered advisers to increase the nature and frequency of reporting to investors, and would prohibit both registered and exempt reporting advisers from engaging in certain activities it deemed contrary to the public interest and protection of investors.

On May 3, 2023, the SEC also adopted amendments to Form PF, significantly expanding the reporting that must be provided by registered investment advisers managing private funds.[xviii] The SEC has also proposed rules related to cybersecurity, outsourcing, ESG investing, and other matters that will impact private fund advisers.

Conclusion

Private funds offer an efficient mechanism for managers and sponsors to raise capital without becoming subject to the onerous cost, reporting, and compliance burdens associated with registered securities or fund offerings, while offering investors access to important asset classes and diversification.

However, private funds do not exist in a regulatory vacuum, and prospective managers should familiarize themselves with the numerous, and often overlapping, patchwork of rules and exemptions that govern private fund operations.[xix] The SEC continues to scrutinize the private fund activities of both registered and exempt managers, especially in enforcement and examinations, so entrants to the market should ensure they structure their funds and ongoing business activities in a compliant manner.

****

*Dominic M. Hulse is a partner at Snell & Wilmer L.L.P. in Denver, Colorado. He has nearly 20 years of international experience advising financial services and investment management clients on fund formations, corporate and securities matters, and derivatives transactions. Licensed to practice in New York, Colorad,o and the United Kingdom, Dominic has counseled investment advisers, banks and financial institutions, private equity and hedge fund managers, and other corporate entities on compliance with regulations affecting a broad range of products and asset classes. Dominic may be reached at dhulse@swlaw.com or 303.634.2081. This article does not seek to provide a comprehensive treatment of every law or regulation that affects private fund advisers.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the IAA. This article is for general information purposes and is not intended to be and should not be taken as legal or other advice.

[i] See https://www.sec.gov/files/2022-pf-report-congress.pdf at page 2. This represents nearly triple the assets reported by advisers in 2013.

[ii] See, e.g., https://www.sec.gov/files/2023-exam-priorities.pdf and https://www.sec.gov/news/press-release/2022-206.

[iii] While exemptions are available from registration as a commodity trading advisor or commodity pool operator under the CEA, they are beyond the scope of this article.

[iv] 17 C.F.R. § 230.501 et seq

[v] 17 C.F.R. § 230.506

[vi] 17 C.F.R. § 230.501(a)

[vii] 15 U.S.C. § 80a–3 et seq

[viii] The SEC noted in the adopting release for Rule 506(c) that it historically has regarded Rule 506 transactions as non-public offerings for purposes of Sections 3(c)(1) and 3(c)(7), and that a private fund may engage in general solicitation in compliance with Rule 506(c) without losing either of the exclusions under the 1940 Act. See Eliminating the Prohibition Against General Solicitation and General Advertising in Rule 506 and Rule 144A Offerings, Rel. No. 33-9415 (July 10, 2013).

[ix] While Section 3(c)(7) does not apply a numerical limit to the number of “qualified purchasers” in a fund, prospective managers should consider the application of (i) publicly traded partnership tax rules and (ii) Exchange Act reporting requirements when determining the number of investors to accept into a fund. Substantive discussion of these topics is beyond the scope of this article.

[x] In no-action relief provided to Redwood Trust Inc., dated October 2017, the SEC staff noted that “the exclusion in Section 3(c)(5)(C) may be available to an issuer if: at least 55% of its assets consist of ‘mortgages and other liens on and interests in real estate’ (called “qualifying interests”) and the remaining 45% of its assets consist primarily of ‘real estate-type interests;’ at least 80% of its total assets consist of qualifying interests and real estate-type interests; and no more than 20% of its total assets consist of assets that have no relationship to real estate.”

[xi] 5 U.S.C. § 80b–2 et seq

[xii] 17 C.F.R. § 275.203(l)-1

[xiii] 17 C.F.R. § 275.203(m)-1

[xiv] 17 C.F.R. § 240.3a4-1

[xv] 17 C.F.R. § 206(4)-1

[xvi] See SEC Staff Marketing Compliance Frequently Asked Questions (Jan. 11, 2023), available at https://www.sec.gov/investment/marketing-faq.

[xvii] https://www.sec.gov/rules/proposed/2022/ia-5955.pdf.

[xviii] https://www.sec.gov/rules/final/2023/ia-6297.pdf.

[xix] In addition, advisers should also consider whether and how other regulations including, but not limited to, ERISA, Exchange Act trade reporting, and state privacy laws, apply to the adviser or private fund.

The private fund industry has undergone significant growth over the past decade, with net assets reported by advisers exceeding $14 trillion as of the second quarter of 2022.

The private fund industry has undergone significant growth over the past decade, with net assets reported by advisers exceeding $14 trillion as of the second quarter of 2022.